Hacking accessibility at w00tcamp

Building a product that helps deaf people have conversations with people that don’t know sign language

Last weekend we had w00tcamp at Q42. Our yearly hackathon where we bundle all our technical interests and entrepeneurship to build amazing products, in two days.

I joined the team of our accessibility expert Johan Huijkman. He wanted to build a product that helps deaf people have conversations with people that don’t know sign language. A noble cause, and fun tech because he wanted to use the Microsoft HoloLens to achieve this goal. The HoloLens would allow the deaf person to see a sign language interpreter as a hologram in the real world. The interpreter could be placed on screen in spot so that the deaf person could simultaneously watch their conversation partner and the interpreter. Also on the team were Thijs Suijten and Bas Peschier.

Skype on the HoloLens

So we started with checking out what was already available. It turns out that Skype has an awesome HoloLens application, where both parties can even draw on the 3D space that the HoloLens is pointed at. We put in a couple of hours to try to make an interface on the HoloLens that would match deaf people to on-call interpreters. When the match is made, we wanted the app to open Skype for the actual videoconferencing.

We encountered a number of obstacles. First of all, you can’t open the Skype app from within another application. There’s no <a href=”skype:”>. Our next attempt was to have the interpreter call the HoloLens. Turns out that when you’re inside another app in the HoloLens and you get a Skype call, you don’t get a visual cue. Only Cortana whispers in your ear that you can say “answer” to pick up the phone. Unfortunately, our HoloLens user is deaf so she won’t hear Cortana…

Another interesting dilemma was that Skype flipped the image. We hadn’t noticed until Eva, who is deaf, joined our team on day 2. When she put on the HoloLens, she immediately saw that the the sign language was RTL. This problem was fixable; we took down a toilet mirror to do it :)

Building the prototype

At the end of day one we had encountered so many obstacles, knowledge gaps and progress bars (I’m talking to you, Windows Updates!) that we decided to build the prototype with web technologies instead of on the HoloLens itself.

What we needed was pretty basic. A webpage where interpreters log in to answer requests, and a webpage where deaf people go to and request an interpreter. And then, of course, the video conversation when a match is made.

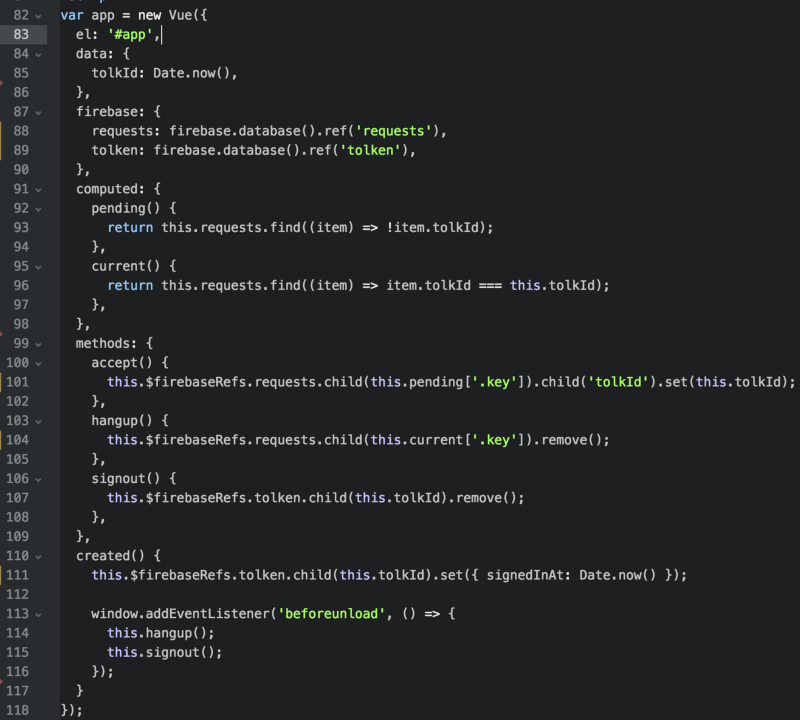

For the first part we decided upon Firebase. Quick to setup, free, and I had some experience with it. But it’s not w00tcamp if you don’t throw in some new technology. So we used VueJS, and a vuefire package that combines the two. It took a little while to wrap my head around it, but that’s only because I didn’t expect it to be so simple. Here’s the code for the interpreter screen. Without 80 lines of HTML and CSS.

If you’re familiar with VueJS you’ll recognize most of the code. Vuefire adds the firebase attribute, where you declare the nodes in the firebase tree that you want to monitor. The content of these nodes are monitored and cached in an array, in this case this.requests and this.tolken. If you want to modify these nodes, you can use this.$firebaseRefs.

All in all this is actually readable code! And it’s just a normal HTML file statically hosted on Firebase. I like the setup, and will probably use it more often.

Thijs focussed on the video conferencing, and ended up with an implementation of https://appr.tc/, but then self-hosted on an Ubuntu VM so he had complete control over the interface and make it custom for our usecase.

The result

Our demo was pretty neat. Eva started on stage with the HoloLens on. In it she saw her sign language interpreter and could understand people in the audience. That is, in theory, because the internet connection was so dramatic that they lost contact all the time…

Johan demo’d the interface that a deaf person would use to connect to an available interpreter. Pretty simple, just one big “help me out” button that opens a video screen.

Now what?

We had hit upon a concept that doesn’t exist yet. Eva pointed us to a number of services that can help her out on the phone, or in person. But she would really be helped out if she could request assistance of a sign language interpreter via videoconferencing on her phone (or, in the future, glasses).

We have a prototype and a rough outline of a business model. Who knows, this might be an existing service in a couple of months time!